What are congenital cataracts? Symptoms, Causes, & Treatment

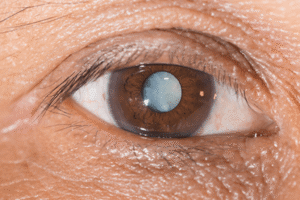

Cataracts are often associated with aging, but did you know that some babies are born with them? These are known as congenital cataracts, and while they are rare, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to protect a child’s vision.

In this blog, we’ll explain everything you need to know about congenital cataracts — from causes and symptoms to available treatment options and long-term outlook.

Table of Contents

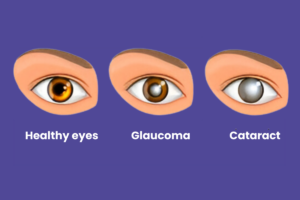

ToggleWhat are congenital cataracts?

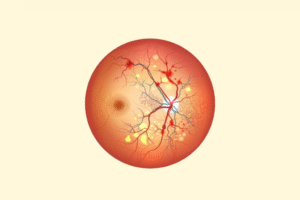

Congenital cataracts refer to a clouding of the eye’s natural lens that is present at birth or develops within the first year of life. The lens, which is normally clear, plays a vital role in focusing light on the retina to produce sharp images. When it becomes cloudy, it can block or distort vision — potentially leading to permanent visual impairment if not treated promptly.

Congenital cataracts can affect one eye (unilateral) or both eyes (bilateral) and vary in size, shape, and severity.

Symptoms of congenital cataracts

Since babies can’t communicate vision problems, it’s important for parents and doctors to watch for signs:

Visible signs:

- White or gray pupil (leukocoria)

- Eyes not focusing on objects or faces.

- Wandering eye movements (nystagmus)

- Misaligned eyes (strabismus)

- Poor visual response or visual tracking.

In older infants:

- Clumsiness or difficulty recognizing familiar faces.

- Lack of interest in toys or surroundings.

- Delayed visual milestones.

Vision is developing rapidly in the first few months of life. Any delay in treating visual obstructions can lead to amblyopia (lazy eye) or even irreversible blindness.

What causes congenital cataracts?

The causes can be genetic, metabolic, infectious, or even trauma-related. Sometimes, the exact cause remains unknown (idiopathic).

Common causes include:

- Genetic mutations/inherited disorders (e.g., Down syndrome, Lowe syndrome).

- Intrauterine infections during pregnancy (e.g., rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex).

- Metabolic diseases (e.g., galactosemia)

- Chromosomal abnormalities

- Maternal drug use or alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

- Eye trauma (if cataract develops shortly after birth).

Diagnosis of congenital cataracts

Congenital cataracts are often identified:

- During routine newborn eye exams.

- At pediatric visits if parents or doctors suspect vision issues.

- Using tools like:

- Red reflex test

- Slit-lamp examination

- Ultrasound of the eye

- Genetic and metabolic testing (if needed)

Early detection, ideally within the first 6-8 weeks of life, plays a key role in achieving better outcomes.

Treatment options for congenital cataracts

Early and appropriate treatment is crucial to prevent permanent vision loss caused by congenital cataracts. Treatment decisions are based on the size, location, and severity of the cataract, as well as whether one or both eyes are affected.

1. Observation (For non-visually significant cataracts)

Some congenital cataracts are small, located at the periphery of the lens, and do not interfere with the visual axis. In such cases, ophthalmologists may recommend:

- Regular eye examinations to monitor changes in size or density.

- Visual development assessments.

- Delaying or avoiding surgery unless the cataract starts to impair vision.

This approach is common when the cataract is not progressive and poses no threat to visual development.

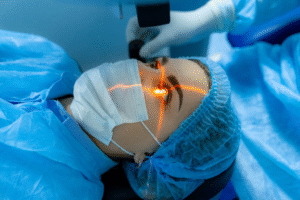

2. Surgical treatment (Mainstay for visually significant cataracts)

If the cataract is dense, centrally located, or blocking vision, surgery is the only effective treatment. Timing is critical — delays can lead to amblyopia (lazy eye), strabismus, and irreversible visual impairment.

a. When is surgery performed?

- Unilateral (one eye) cataracts: Ideally within 4 to 6 weeks of age.

- Bilateral (both eyes) cataracts: Within 6 to 8 weeks.

Earlier surgery is associated with better visual outcomes, especially when followed by proper visual rehabilitation.

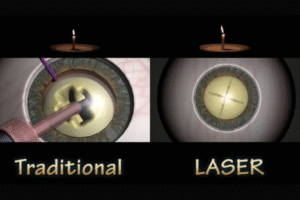

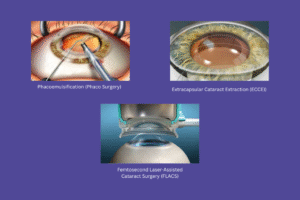

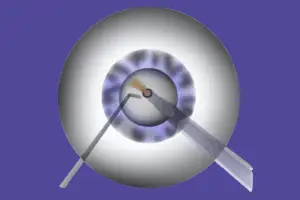

b. Surgical procedure

The surgery is performed under general anesthesia and includes:

- A small incision is made in the eye.

- The cloudy lens is carefully removed.

- In infants below 1 year, intraocular lens (IOL) may or may not be implanted immediately (based on surgeon’s judgment and clinical guidelines).

- The eye is then sealed with sutures or allowed to self-seal.

Surgery is often daycare-based, and recovery is generally smooth if postoperative care is followed.

3. Post-surgical visual rehabilitation

Removing the cataract solves the opacity problem, but additional vision support is essential to allow the eye to focus and develop normally.

a. Optical correction

Depending on whether an IOL was implanted:

- With IOL: The child may still need glasses for precise vision correction.

- Without IOL: Optical correction is done using:

- Contact lenses (often preferred for younger babies)

- Thick eyeglasses

Refractive power will need to be adjusted as the child grows.

b. Amblyopia management (Patching therapy)

If one eye was significantly weaker or untreated longer, it may develop amblyopia. In such cases:

- The stronger eye is patched for several hours daily.

- This forces the weaker eye to function, promoting neural development of vision.

This therapy may be needed for months or even years, with regular progress checks.

c. Follow-up & Long-term monitoring

After surgery, children need:

- Frequent eye check-ups, initially every few weeks

- Monitoring for:

- Secondary glaucoma

- Visual axis opacification

- Retinal or optic nerve problems.

- Proper growth of eye structures.

Glaucoma is a common long-term complication of pediatric cataract surgery and must be caught early.

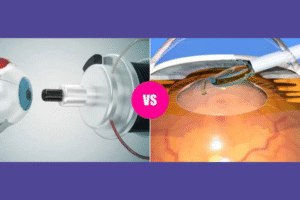

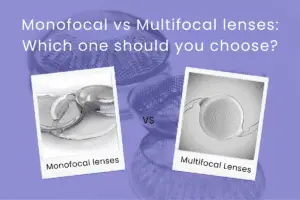

4. Intraocular Lens (IOL) implantation: When & Why?

While adult cataract surgeries routinely involve IOL implantation, it’s more complex in infants.

Considerations for IOL:

- For children older than 1 year, IOL implantation is more commonly done at the time of surgery.

- In infants younger than 6–12 months, the eye is still growing rapidly, and long-term outcomes are still being studied.

- In such cases, the surgeon may prefer to delay IOL implantation and manage vision with contact lenses until the child is older.

A secondary IOL can be implanted later during a separate surgery, once the eye has matured enough.

5. Supportive therapies

- Low vision aids (if vision is not fully restorable).

- Occupational or developmental therapy (for visual development delays).

- Parental guidance and training to manage daily care, therapy, and patching.

In summary, the treatment of congenital cataracts is multi-disciplinary and long-term. Surgery is only one step in a broader care plan that involves vision correction, amblyopia management, and consistent follow-up. The earlier the intervention, the better the prognosis.

Long-term outlook & prognosis

With early diagnosis and proper treatment, many children go on to develop functional vision. However, lifelong monitoring is often necessary to check for:

- Secondary glaucoma

- Refractive errors

- Visual developmental delays

Early intervention and family support are critical to help children lead normal, fulfilling lives.

Conclusion

Congenital cataracts may seem daunting, but early intervention can make a life-changing difference. If you notice anything unusual in your baby’s eyes or if your family has a history of eye disorders, don’t delay an eye check-up.

At Krisha Eye Hospital, Ahmedabad, our experienced pediatric ophthalmologists specialize in early detection and surgical management of congenital cataracts. We offer comprehensive care tailored to your child’s needs — from diagnosis to vision rehabilitation.

Contact us today to book an appointment or learn more about pediatric eye health.

Author bio

Dr. Dhwani Maheshwari, an esteemed ophthalmologist with over 10 years of experience, leads Krisha Eye hospital in Ahmedabad with a commitment to advanced, patient-centered eye care. Specializing in cataract and refractive surgery, Dr. Maheshwari has performed more than a thousand successful surgeries. Her expertise lies in phacoemulsification, a technique recognized for its precision in cataract treatment.

Dr. Maheshwari’s educational journey includes an MBBS from Smt. NHL MMC, a DOMS from M & J Institute of Ophthalmology, and a DNB in Ophthalmology from Mahatme Eye Bank Eye Hospital, Nagpur. She also completed a fellowship in phacoemulsification at Porecha Blindness Trust Hospital, further enhancing her surgical skills. In addition to her work at Krisha Eye Hospital, Dr. Maheshwari serves as a consultant ophthalmologist at Northstar Diagnostic Centre.

Under her leadership, Krisha Eye Hospital aims to bring all superspecialties under one roof, offering comprehensive eye care solutions for all vision needs.

FAQs

Yes, congenital cataracts can be hereditary. They may be passed down through genes and can occur as part of genetic syndromes. However, not all cases are inherited—some are caused by infections or metabolic disorders during pregnancy.

They can be detected soon after birth during a newborn eye screening or within the first few months of life. Pediatricians and ophthalmologists look for signs like absent red reflex or abnormal eye movements.

No. If the cataract is small and not affecting the visual axis, it may not require surgery. Observation and regular follow-up are done to monitor progression. However, if the cataract affects vision, surgery is usually recommended.

Surgery is typically done within the first 6–8 weeks of life for best visual outcomes—sooner for cataracts in one eye. Timing is critical to prevent amblyopia (lazy eye) and promote normal visual development.

Many children can achieve good vision, especially if the cataract is treated early and followed by proper visual rehabilitation (glasses, contact lenses, patching). Long-term follow-up is essential to manage complications like glaucoma or visual axis opacification.

In some cases, yes. However, IOLs are more commonly implanted in children over 1 year of age. For infants, surgeons may delay IOL placement and use contact lenses or glasses until the child’s eye matures.

The cataract itself doesn’t “come back,” but posterior capsule opacification (PCO)—a clouding behind the lens implant—can occur and may require laser treatment or additional surgery in some cases.

Yes, some children may develop secondary glaucoma, strabismus, or refractive errors over time. Regular follow-up is important to detect and manage these issues early.

Not always. But risks can be reduced through good maternal care during pregnancy, managing infections like rubella, and undergoing genetic counseling if there’s a family history of eye conditions.